This is the third post in my series on meaningful engagement. You can check out the other two posts in the series here:

- Meaningful Engagement vs. Buy-In: What's the Difference and Why Should I Care?

- What's the Driving Force Behind Engagement?

Meaningful engagement and the co-creation of change can produce much more commitment than simple buy-in can.

Organizations that settle for buy-in, rather than aspire to meaningful engagement, miss out on the opportunity to:

- Deepen commitment to the change process

- Stimulate co-creation of solutions

- Build business literacy and other important business skills, and

- Accelerate the pace of change.

I define meaningful engagement as:

“Any authentic involvement that allows people to make consequential contributions to the process and the outcome of a change and deepens their understanding of it, their commitment to it, and their ownership of it.”

As I wrote in Meaningful Engagement vs. Buy-In: What's the Difference and Why Should I Care?, leader commitment – including the belief that ordinary people can make extraordinary contributions and the willingness to commit time, effort, and resources to enable them to do so – is the pivotal difference between enabling meaningful engagement and settling for buy-in.

Without a leader’s resolute commitment to authentic involvement, the full measure of meaningful engagement will not be realized.

If we know that meaningful engagement is what we want and need in our organizations, how do we go about creating it?

What Might Engagement Opportunities Look Like?

Before we come to the 4-step process for creating meaningful engagement in your organization, a little context for what engagement opportunities might look like is helpful.

Meaningful engagement, like change in general, does not happen by accident.

Helping people make consequential contributions to the process and outcome of change requires clear intent.

By the definition above, any authentic involvement that allows people to make consequential contributions constitutes meaningful engagement. This opens a wide range of opportunities for creating engagement.

Because the range of opportunities is broad, I find it helpful to group them into three categories. These categories align with the breadth of a change effort and the examples lend themselves to widespread engagement.

Example #1: Using temporary teams to collect data and analyze the current state relative to the desired future state.

Engagement in this early stage might include:

- Collecting “voice of the customer” data.

- Evaluating current customer satisfaction.

- Assessing current state organizational arrangements (structure, processes, technology, etc.).

- Benchmarking aspirational organizations or processes.

- Estimating the current cost of quality.

- Assessing current vs. required future levels of skill, knowledge, and ability, etc.

Because this engagement is happening early in the change process, you may even enlist the help of a temporary team to assess organizational change readiness, impact, risk, and resistance.

An example of this engagement opportunity is an organization that was making major changes to its production system. A mixed team was formed and trained to conduct site visits with non-competing organizations to learn about work system innovations they had designed and implemented.

The team planned and conducted four site visits and made a presentation of their findings to the whole organization. What they learned was integrated into their production system redesign and had a dramatic, positive affect on the eventual outcome of the change.

Example #2: Using temporary teams to address identified gaps and develop viable alternatives of material importance to the change.

When you’re addressing gaps and developing alternatives, consider:

- Employing teams to do organization design (such as creating a new unit to serve a new or expanded function, integrating units to focus effort or eliminate costly redundancy, etc.).

- Process analysis and redesign (to match organizational or other requirements).

- Evaluating and recommending technology or software application solutions.

- Developing and recommending new procedures.

- Creating and proposing development efforts to close skill gaps, and so on.

In an example of this engagement opportunity, a client organization that was focused on accelerating product development suffered from a hiring process that took too long to fill open requisitions and acquire key talent.

A cross-functional team from HR and business units was formed and chartered to work on the matter. The team mapped the as-is process from beginning to end adding information about volume and transaction time to each step. Once they understood their own process and key metrics, the team benchmarked the hiring processes of three non-competing organizations.

In the end, they identified nearly a dozen improvements and simplifications. The team weighed these alternatives, selected the ones they believed would make the greatest difference in the shortest amount of time, and redesigned the process to incorporate these.

Once implemented, the time from requisition to hire decreased by more than 40% over the following six months.

Example #3: Using temporary teams to develop and implement critical solutions.

A technology company that had undergone a large organization redesign was approaching sunset for one of its main products as it prepared to launch a new technology product in its place. With this transition came a significant challenge. The company needed to provide an adequate supply of field-replaceable spare components for up to seven years to support existing customers. The need to manufacture and store spare components to preserve this length of shelf life presented a problem not encountered in the industry before.

A cross functional team was formed consisting of representatives from packaging, production testing, process engineering, production control, mechanical engineering, test equipment maintenance, and other engineering groups. The team was charged with investigating the feasibility of long-term storage and, if feasible, developing and recommending an implementable packaging and storage solution.

Having been fully engaged in the large organization change, the team applied the skills they had learned to organize themselves and plan and execute their work. Over a period of nine months, the team in fact identified a feasible packaging and storage method for long-term storage of this delicate electronic component and developed a procedure that could be applied immediately.

By the tenth month after the team was formed, all field-replaceable spare components were being packaged and stored according to the new method. The new method provided immediate improvement to the storage and shipment of current spares to customers. In addition, it allowed the company to build ahead and thereby discontinue manufacture of the out-going product earlier than planned which saved $25 million in operations cost.

The 4 Steps to Creating Meaningful Engagement and Deepening Commitment to Change

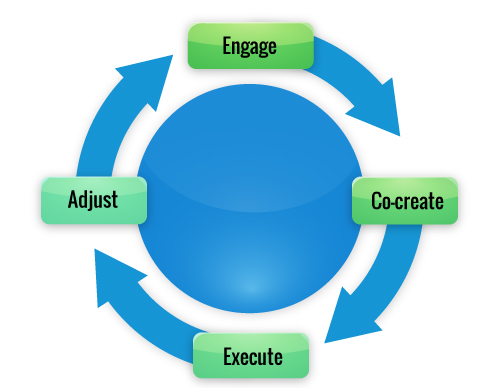

The Engagement Cycle is the framework I use to describe the tactical steps of enabling meaningful engagement.

Let’s talk about how to proceed through each of these steps.

- Engage

Enlist the direct participation of the right mix of people in some issue or action step that will make a consequential contribution to the change.

Consider the phase of the change effort you’re in and choose some element of the project plan for a temporary team to work on. Keep in mind that there will likely be multiple teams working concurrently on different elements of the project plan, with each team each making a planned contribution to the whole.

Select teams that represent the right mix of function, hierarchical level, experience, and expertise.

Charter the teams (purpose, scope, authority, responsibility, time commitment, end date, expected deliverable, etc.) and conduct team launch events to give each team a solid start.

- Co-create

In this step, give your teams the time, resources, and support required to do their work according to their charter.

Allow the teams to:

- Plan their own work schedule, process, and methodology

- Collect data relevant to their assignment

- Develop alternative solutions and prioritize them

- Develop recommendations and plans to implement.

What each team creates and delivers will be a function of what that team is charged to do.

Early in the change, for example, a team’s work may be an input to the business case for change or an assessment of some sort. Such a deliverable wouldn’t require implementation.

Later, when executing change, a team’s work may deliver a critical component of the change, e.g. a technology or application recommendation, the creation of a new organizational unit, a redesigned process, or a new procedure.

- Execute

If the team has been chartered to develop and deliver a component that is integral to the change, then in this step the team presents its recommendation(s) and implementation plan (if required by its charter) to leadership or the appropriate oversight body.

Once approved, the recommendation(s) and implementation plan are socialized with those affected and feedback is solicited.

Implementing the recommendation(s) is the main event in this step. The team may broaden engagement at this point and enlist additional support to put the recommendation in place and begin monitoring its efficacy.

- Adjust

In this step, everyone who was involved in developing and implementing this component of the change operates it as planned and implemented for a specified time.

The people involved in implementing the change monitor the solution and collect relevant data about its performance.

Based on experience and performance data, they develop refinements and improvements, as needed.

If necessary (and perhaps on a reduced scale), they may repeat the cycle of engage, co-create, execute, and adjust.

Using the Engagement Cycle in Your Organization

The Engagement Cycle can be used repeatedly across the phases of the change effort to engage multiple teams in making consequential contributions. This process can also be used to refine and improve a particular element of the change.

The Engagement Cycle is similar to the way organizations use temporary teams to address particular problems or take on initiatives. The chief difference is in joining multiple teams’ efforts to the change plan and permitting them to co-create the change every step of the way.

There is nothing fancy involved here – no magic formula or secret sauce. It is the following potent combination.

- The leader’s belief that ordinary people can make extraordinary contributions if given the chance plus

- A systematic approach to enable meaningful engagement

If you’d like to learn more about how you can take your change work to another level, please visit thechangekit.com.