In my previous post Meaningful Engagement vs. Buy-In: What's the Difference and Why Should I Care?, I posed two questions.

- “… why do we continue to manage change in ways that do not truly engage people and foster conditions where “meaningful engagement” can occur commonly?

- Why do we continue to settle for “buy-in” when we want and actually need much more?"

I suggested five reasons why many organizations settle for buy-in rather than aspire to meaningful engagement. I refer you to the previous post for the specifics (Buy-In vs. Engagement: What’s the Difference and Why Should I Care?). Briefly, though, I argued that buy-in more often triumphs as the objective of change management because it doesn’t require the same level of leader or manager commitment that meaningful engagement does. Aiming for buy-in just doesn’t demand as much time and effort and, in the end, unfortunately, expedience wins.

BUT, and it’s a big but, I argued that tacit buy-in doesn’t produce nearly as much commitment as meaningful engagement and the co-creation of change can. Done right, meaningful engagement in organizational change has the potential to:

- Strengthen everyone’s understanding of the need for and direction of change

- Deepen commitment to the change process and objectives

- Stimulate co-creation of solutions

- Build business literacy and other important business skills

- Accelerate the pace of change, and

- Propel the change beyond the envisioned outcome

In this post, we’ll continue this exploration of meaningful engagement and pose two additional questions.

- How does meaningful engagement produce more than simple buy-in?

- What are the dynamics at work?

Concepts

Answering these two questions requires dipping our toes into the theory pool for a few paragraphs. I promise this will not be painful, but it is important.

I’m going to assume that most change management practitioners know that Kurt Lewin, Margaret Mead, and a host of very talented people did the seminal work in social change as part of the war effort during World War II. A major challenge for the War Department at the start of the war (which the Department believed might be waged for as long as 10 years) was to ensure sufficient food supplies to feed our troops on two fronts, our allies’ troops on the European front, and the American homeland. As one of a variety of efforts in this direction, the challenge presented to Mead and Lewin by the War Department was to determine how to change the consumption habits of Americans to incorporate non-traditional meats. If you are unfamiliar with this work, I strongly recommend reading Group Decision and Social Change by Kurt Lewin in Readings in Social Psychology, ed. Newcomb and Hartley, 1947. It will acquaint you with key concepts that underpin change management to this day.

Lewin, a social psychologist, was a proponent of field theory. He believed human behavior is a function of a variety of forces acting on an individual in a setting referred to as a “field.” Forces have differing strength and valence – that is, some are positive and attract while others are negative and repel. An individual’s decision to take action in some particular direction is influenced by the sum of strength of these forces and their valences.

In the food habit studies that Lewin and others conducted beginning in early 1942, Lewin applied a simplified version of field theory that we have come to know as force field analysis. The change target – in this case the predisposition of housewives to prepare and serve dishes incorporating non-traditional meats – is in a state of equilibrium or “no change.” There are forces that are acting to move the equilibrium in the direction of making the change, e.g. a sense of patriotic duty, nutritional value of the meats, greater availability of these meats at lower prices, etc. Lewin called these driving forces.

There are also forces that are acting in the direction against making the change, e.g. unfamiliarity with preparing dishes using these meats, the smell and texture of these meats, the family’s distaste for such dishes, etc. Lewin called these restraining forces.

Lewin suggested there were two ways to make change. First, you could add driving forces to move the equilibrium in the intended direction. Second, you could diminish or remove restraining forces. In each case, the equilibrium is broken and change in the desired direction will result. However, there are material differences for the consequence of the approach. Only applying force in the intended direction sets up counter forces and results in greater tension in the system along with other negative consequences.

Sound familiar? Change imposed is change opposed.

In this seminal work, Lewin identified a number of concepts associated with understanding and intentionally creating change that still inform our change work today. For the purpose of this entry I want to focus on three.

- First is the concept of the change target as equilibrium – a stable but addressable state

- Second is force field analysis. We can identify and represent the forces acting on a state of equilibrium and plan how to move the equilibrium in the desired direction by adding driving forces, reducing or eliminating restraining ones, and by doing both together.

- Third is “group-carried” as opposed to individual change. To quote Lewin, “It is easier to change the ideology and social practice of a small group handled together than of single individuals.”

The Case for Meaningful Engagement

Sometime later these foundational concepts were put to use in an experiment with a garment manufacturer that was having chronic trouble with high turnover, numerous grievances, restricted production, and aggression toward management. The situation was driven by the nature of the business, e.g. frequent product changes (style, season, material, etc.) necessitating frequent transfers of workers to new job assignments and new work groups.

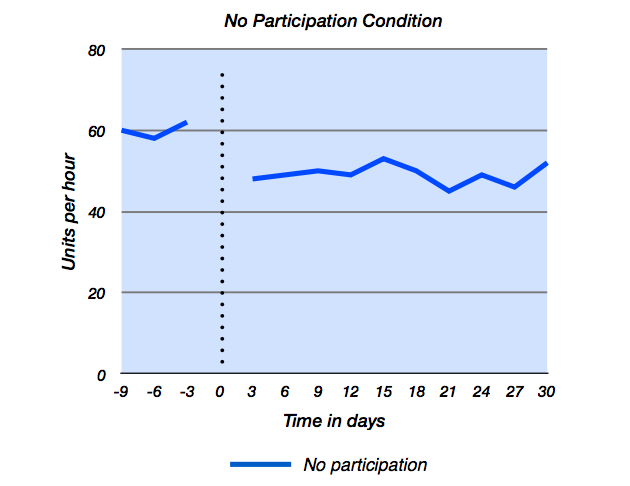

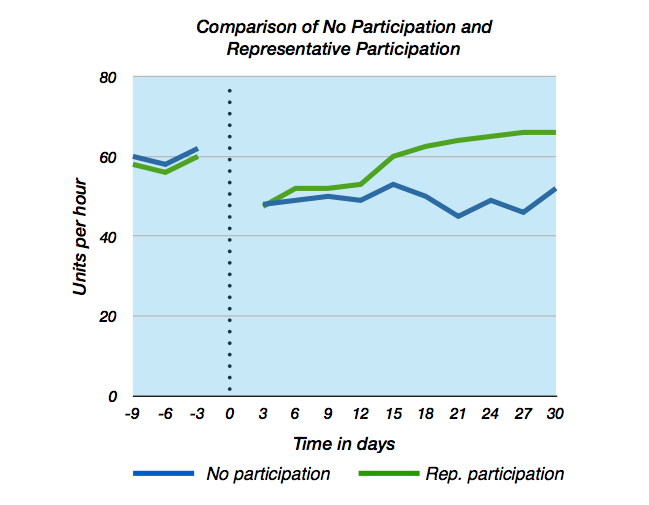

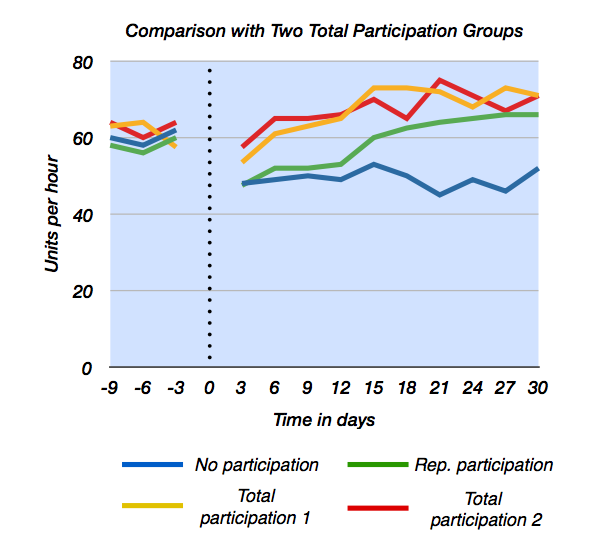

Reassignments resulted in disruption to important aspects of the individual’s work experience including primary co-worker relationships, the job itself, and, most importantly, wages. Since workers were paid by the piece and the plant production norm was 60 pieces per hour, a new assignment meant immediate loss of proficiency and lower wages until proficiency to the group standard recovered.

An experiment was devised for making changes using three levels of participation in job changes.

Condition 1: No participation by workers in planning the change

An explanation of the change was provided, but beyond that workers were reassigned in the usual way.

Condition 2: Representative participation in planning the change

This consisted of the following steps:

- Demonstrate the need for the change to the whole group

- Perform a review of the job to eliminate unnecessary work (process improvement)

- Train representative operators (chosen by the group) in the correct method of the new job

- Establish a new piece rate based on the performance of these trained operators

- Have the trained operators explain the job and new piece rate to their co-workers and train them.

Condition 3: Total participation by all members of the group in planning the change

There were two of these groups. The initial steps of holding a meeting to demonstrate the need for change and a review of the job to eliminate unnecessary work were identical. The process diverged at this point. Instead of training representatives, all members of each group were invited to participate directly in designing the new job. Numerous suggestions for process improvement were made during this time. When team members had settled on the job design, a time study to establish a new piece rate was applied to all operators.

Piece rates were collected for all groups prior to the experiment beginning and all hovered around the standard of 60 units per hour.

The “no participation” group (blue line) showed no progress beyond their initial productivity rate, which was below production standard (60 units per hour) in the first 32 days. Resistance to the change developed almost immediately marked by expressions of aggression against management, conflict with engineers, hostility toward supervisors, and eventual restriction of production. Voluntary separations at the end of the experiemental period amounted to 17%.

The representative participation groups (green line) showed a good relearning curve and achieved the target piece rate in about 14 to 16 days and continued to operate above the norm for the duration of the study. Workers’ attitudes were cooperative and no one quit in the first 40 days.

The representative participation groups (green line) showed a good relearning curve and achieved the target piece rate in about 14 to 16 days and continued to operate above the norm for the duration of the study. Workers’ attitudes were cooperative and no one quit in the first 40 days.

The total participation groups (red and gold) recovered much faster than either of the other two conditions. By Day 5, one of the two groups was functioning at 8% above the target piece rate. By Day 15, both groups were functioning at 25% above the target piece rate and remained there during the duration of the study.

The total participation groups (red and gold) recovered much faster than either of the other two conditions. By Day 5, one of the two groups was functioning at 8% above the target piece rate. By Day 15, both groups were functioning at 25% above the target piece rate and remained there during the duration of the study.

A second experiment was performed with the remaining members of the no-participation group. Another job change was initiated using the total participation technique and this resulted in the same outcome as the total participation groups in the first experiment. Operators recovered quickly to their previous efficiency rate and by Day 8 settled into the new production rate of around 70 units per hour.

A second experiment was performed with the remaining members of the no-participation group. Another job change was initiated using the total participation technique and this resulted in the same outcome as the total participation groups in the first experiment. Operators recovered quickly to their previous efficiency rate and by Day 8 settled into the new production rate of around 70 units per hour.

The first experiment showed that rate of recovery, ultimate rate of production, reduction of grievances, aggression, and voluntary separation were all positively associated with the level of participation and that the greater the level of direct participation the greater the effect. The second experiment reinforced the conclusion that the effect is a function of the experimental treatment – total participation – rather than skill, selection of groups, or other personality factors.

What happened and what’s driving the differences?

Let’s return to Lewin’s concepts of change target as equilibrium and force field to explain what happened and what’s at work.

Any change target is an equilibrium – a stable but addressable state – that exists in a field of forces acting in dynamic balance to hold it in place. The change target in the case was the level of production. The plant production norm hovered around 60 units per hour and represented a dynamic balance between upward forces from management to increase production and downward forces experienced by operators such as difficulty of the job, skill level, the amount of physical strain required over time, and social norms to conform.

When job re-assignment occurred, the equilibrium was disrupted in a very negative way – arbitrary re-assignment, no explanation of the necessity for the change, job tasks, method, and piece rate imposed by the production department. This had the effect of setting up additional downward forces that slowed recovery and resulted in hostility, grievances, and turnover. This very same dynamic played out in the no-participation group.

When change is dictated in this way, it represents an “induced” force – an order or demand to do a particular thing. As each of us has experienced, induced forces may have different impacts on us and the impacts depend upon who is doing the inducing and what our relationship is to them. If someone we like is doing the inducing – a friend or someone we trust and to whom we have attributed legitimate authority – then the induced force may be accepted as if it were an “own” force – one that would grow out of one’s own internal desires.

However, if the induced force is delivered by someone we don’t particularly like or some group with whom we have an untrustworthy, negative, or contentious relationship then an induced force will likely be rejected. You still do what is required of you (because it is a condition of employment so long as you remain), but you will not do it as if it had grown out of your own desire.

We come now to the question posed in the title of this post – “What’s the driving force behind engagement?” The answer is this.

An induced force that is accepted generates additional “own” forces in the same direction. An induced force that is rejected generates additional “own” forces in the opposite direction. In both cases, accepted and rejected forces are reinforced by the social dynamics of the group to which an individual belongs and become part of its ideology and social practice.

If you want commitment to change, then you want an induced force to be accepted and to become an own force and you want to do this in the context of a group.

How do we get there?

Organizations that place any importance on change management generally will not make a Condition 1, no participation change. Even as I write this, though, I know there is lot of Condition 1 change in the organizational world. It’s easier than more participative approaches. Declare a change and let others muck around in the details. Condition 1 change can seem fast and appear tidy on the surface. But as we’ve seen, there are negative consequences below the surface that may live on for a long time.

However, organizations that place some level of importance on change management will most often choose buy-in as the operating approach for making change. This approach, I would suggest to you, looks much more like Condition 2. See if the following doesn’t sound familiar to you.

The effort usually begins with an initial communication about the need for change – what we might commonly refer to as the business case. It may be as simple as an organization-wide announcement that change is coming and what will happen next or it may be more elaborate. I’ve seen several organizations effectively use strategy maps in a workshop setting as a vehicle to involve employees in a discussion of the business case for change. The intent of this initial step is “buy-in.” In the previous post I defined this as agreeing that the change is worthwhile and consenting to what comes next.

What often comes next is this.

Managing the change effort typically becomes the responsibility of a team of people such as a design team, change team, or a project management office who are highly involved in working out the details for the change. In some cases, there may be more than one of these teams. These people get to have a Condition 3 experience. Everyone else does not.

There is regular push communication aimed at preserving momentum and buy-in. Eventually, organization members are informed of what will happen when. Where necessitated by the change, they are informed that they will receive training to perform their job in the new system. However, in most cases, they will not experience anything like Condition 3 where they would have a direct hand in designing the organization, the supporting processes, or any other feature of the change.

Change happens in this case, but I would assert that the results look more like Condition 2 than Condition 3, though better than Condition 1.

Look at the charts above again. In the Representative Participation condition, it took half of the experimental period to recover to the previous level of proficiency and the second half to approach the new Condition 3 level. If a fundamental goal of change management is to reduce the depth and duration of what is called the “J” curve, then a buy-in approach that approximates Condition 2 in many ways is less than what we want.

We want Condition 3 results from our change efforts. And the preferred outcomes are what I enumerated at the beginning of this post.

- Strengthen everyone’s understanding of the need for and direction of change

- Deepen commitment to the change process and objectives

- Stimulate co-creation of solutions

- Build business literacy and other important business skills

- Accelerate the pace of change, and

- Propel the change beyond the envisioned outcome.

We do this through meaningful engagement that drives the co-creation of change and how we accomplish this will be the topic of the third post in this series.

In the meantime, if you’d like to learn more about how you can take your change work to another level, please visit thechangekit.com.